He continues, “It was a chaotic time. I was trying to keep the ship afloat as much as I could while allowing Corinna to recover. I would follow the doctors wherever they took my daughter. I was getting so many questions from our family.”

And Layla wasn’t getting better. She couldn’t breathe on her own and, on top of everything else, came down with meningitis. By then, Corinna and Dmitry faced another fork in the road: stay the course, or transfer Layla to Seattle Children’s Hospital for another opinion. They chose to move her.

At Seattle Children’s, Layla’s care team asked her family to join the SeqFirst-Neo research study. This study offered rapid genome sequencing (rGS) to infants in the NICU whose medical issues were not fully explained by other factors in an effort to determine the benefit of broad spectrum testing for certain babies. For Corinna, the answer was a no-brainer.

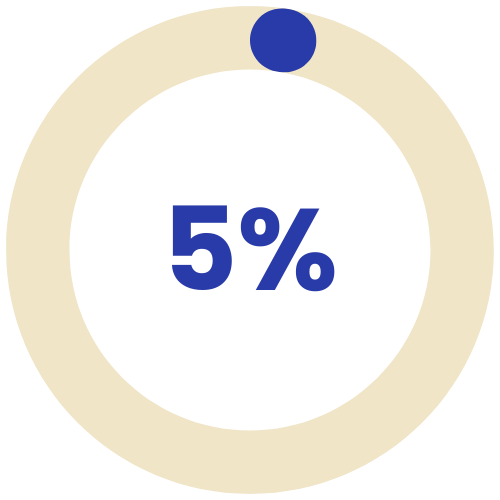

Access to rGS in the NICU isn’t always the norm, despite evidence that testing can save lives. Case in point: the results of the SeqFirst study show that 60% of the babies in the Level IV NICU could benefit from getting genomic testing, yet only 5% do.1,2

Being part of the 5% made all the difference. Just a few days later, they got the results: Layla had a condition called TTC7A deficiency—a rare genetic condition that affects both the intestines and the immune system. Fewer than 80 cases are known worldwide.

“I remember the genetic counselor saying, ‘Don’t Google this.’” Corinna says. “Which, of course, we did. It was terrifying. It is an extremely rare disease.” She adds, “What we found online was heartbreaking. Most of the cases have a very poor prognosis with many children passing away within a year. But we also learned that the outlook can depend on the specific mutation—and Layla’s is unlike anyone else’s.”

For Layla, getting a diagnosis changed everything. It helped her parents and doctors understand how to protect her immune system and adjust their approach. She was quickly moved into isolation, started getting plasma infusions (Hyzentra), and began a more personalized treatment plan. “Without that diagnosis,” Dmitry explains, “they would have treated her like a typical short-bowel patient.”

Corinna adds, “I think there are many more cases of TTC7A. There are so many kids with short-bowel syndrome who also have recurring infections and compromised immune systems. I think because it is such a rare disease, it’s just not something that gets tested for regularly.”

“If something feels wrong, it probably is,” Corinna says. “Ask questions. Push for answers. You are your child’s best advocate. Nobody is going to ask those questions for you.”

“Obviously, there are situations where a decision needs to be made on the spot … you get heartbreaking news, you don’t really know what’s going on, and you are under the impression that you need to make decisions right then and there,” Dmitry says, “but I wish I asked for more time to process everything. Then I would have made better decisions.”

Four years later, Layla is in preschool and enrolled in ballet. She runs, plays, loves the beach, and makes friends wherever she goes. Her mom describes her as spunky, outgoing, and strong-willed. “She does not have a shy bone in her body,” Corinna says.

Layla still uses an ileostomy bag and receives IV nutrition every night, and she gets Hyzentra infusions every two weeks. But to Corinna, it’s a small price to pay. “It lets her live a normal toddler life during the day,” she says. “She can run around and play without being attached to pumps and things.”

And there’s even more reason for hope. A researcher who specializes in TTC7A told Corinna that Layla is one of the top three best cases in the world. “That is very reassuring to hear, because when your child has a rare disease, you have no idea what their life is going to be like. You try and compare your child with other kids, but you really can’t, because every child is so different,” she says.

It’s just one more reminder that she and Dmitry made the right call when it mattered the most. “Now we now know what caused this,” Corinna says, “and we have a path forward to help Layla live her best life.”

Inspired to share your story?

References: 1. Wenger T, Scott A, Kruidenier L, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2025; 112, 1–15. 2. Kingsmore, Stephen F et al. NPJ genomic medicine vol. 9,1 17. 27 Feb. 2024.